In chapters 118-119 of this particular saga, a conversion polemic occurs. It consists of a religious conflict between a heathen hersir named Dalaguðbrandr hereafter known as Guðbrandr, and the Norwegian King Óláfr Haraldsson, also known as St. Olaf. The saga is fundamentally modeled on the tale recounted by Theodoretos of the Bishop Theophilus and the destruction of the cult of Serapis in Alexandria of the 4th century, so its historicity is in question. Despite this, there are clear heathen undertones to be gleaned from the language and frame of the saga, particularly of the Þórr cult.

The saga describes the king going through the region with an army forcing the populace to take up Christianity, and compelling them by force to destroy their idols and temples. This results in Guðbrandr rallying the local farmers to combat this effort. Guðbrandr says:

(…) at sá maðr var kominn á Lóar, er Ólafr heitir, ok vill bjóða oss trú aðra, en vér höfum áðr, ok brjóta goð vár öll í sundr, ok segir svá, at hann eigi miklu meira goð ok mátkara; ok er þat furða, er jörð brestr eigi í sundr undir honum, er hann þorir slíkt at mæla, eða goð vár láta hann lengr ganga; ok vætti ek, ef vér berum út Þór or hofi váru, er hann stendr á þeima bœ, ok oss hefir jafnan dugat, ok sér hann Ólaf ok hans menn, þá mun guð hans bráðna, ok sjálfr hann ok menn hans, ok at engu verða.

(…) a man had come to Lóar, whose name is Ólafr, and wants to offer us a different faith than we have before, and to break all our gods to pieces, and says thus, that he has a more mighty god and more powerful; and it is a wonder that the earth does not break to pieces under him, when he dares to speak such a thing, or our gods let him go further; and I expect that if we carry Thor out of our temple, where he stands on the farm, and has always been sufficient for us, and he sees Ólafr and his men, then his god will melt, and himself and his men, and that nothing will come of it.

In this statement, there are clear indications that the god is identified with the image, much like what is written in other sagas such as Eyrbyggja saga, Rögnvalds Þáttr ok Rauðs, and Sveins Þáttr ok Finns. It is often denoted that the deity speaks from the image, instructing the worshippers or moving in some capacity. In the context of a Christian polemic, this serves to show a limitation in the divine power of the pagan god, and that the god being worshipped is false, only consisting of matter, unable to defend themselves or their worshippers. This is explicit in the saga, as St. Olaf states:

(…) þú ógnar oss goði þínu, er blint er ok dauft, ok má hvárki bjarga sér né öðrum, ok kemst engan veg or stað, nema borinn sé

(…) you threaten us with your god, who is blind and feeble, and can neither save himself nor others, and can get no way out of the place unless he is carried.

Conversely, we can see an underlying heathen perspective in this methodology of identifying the god with the image, it can be more accurately understood that the god speaks through the image to the worshippers.We know that with the destruction of the image, the god is not destroyed, as Þórr speaks through the images of other worshippers. If the god was destroyed, it would mean a cessation of all communication in every image. In this way we can understand the image as a medium through which the worshipper may commune with the god. The image holds a certain amount of animistic power to the worshipper, which is the reason behind the conclusion to bring Þórr out of the temple to frighten the king and his host. This can be noted by the use of the term hvössum augum — keen or sharp eyes. This is a common depiction of Þórr recounted in poetry, referring to his terrifying and wrathful eyes. In this context, the eyes of the image operate much like that of the evil eye.

This animistic power imbues a certain holiness to the image. This is the reason why the emphasis on the sight of the deity is so crucial to the heathens, because of the power which indwelled in the image, and why Guðbrandr is perplexed at why St. Olaf does not incur the wrath of the gods for his remarks and actions against them. From this it can be gleaned that it was taboo to speak against the gods and to destroy the images of the gods. This is known from other saga literature particularly of Hjalti Skeggjason and his insults to the goddess Freyja, being known as goðgá, that is, blasphemous speech against the gods. Evidence of desecrating divine images and shrines is attested in the earlier Lex Frisionum, and we can presume that this injunction was common in other parts of the heathen world:

Qui fanum effregerit, et ibi aliquid de sacris tulerit, ducitur ad mare, et in sabulo, quod accessus maris operire solte, finduntur aures eius, et castratur, et immolatur Diis quorum templa violavit.

If anyone breaks into a shrine and steals sacred items from there, he shall be taken to the sea, and on the sand, which will be covered by the flood, his ears will be cleft, and he will be castrated and sacrificed to the god, whose temple he dishonored.

Later in the saga, St. Olaf has Guðbrandr’s son as a hostage after their initial exchange, and inquires about the god in their temple. The son gives detail on the image and customs of worship:

Hann segir, at hann var merktr eptir Þór, ok hefir hann hamar í hendi, ok mikill vexti, ok holr innan, ok gert undir honum sem hjallr sé, ok stendr hann þar á ofan, er hann er úti; eigi skortir hann gull ok silfr á sér; 4 hleifar brauðs eru honum fœrðir hvern dag, ok þar við slátr.

He says that he was marked after Thor, and he has a hammer in his hand, and is of great stature, and is hollow within, and made under him was a scaffold and he stands on top of it when he is outside; he does not lack gold and silver on him; 4 loaves of bread are brought to him every day, and there is butchered meat.

These details are fairly straight forward in their presentation here. Of particular note are the daily food offerings. The connotation behind the term slátr is fleshly slaughtered meat, meaning animal sacrifices were given to Þórr on a regular basis. Meat given as sacrifice is called blótmatr, which we know from Hákonar saga Góða. Another use of the term slátr is of a means of payment indicating that this offering was given to Þórr as as his due. A concept that is also present in Flóamanna saga wherein Þórr demands payment from Þorgils, a former worshipper of his:

Þórr svarar: “Þótt þú gerir mér aldri gott, þá gjalt þú mér þó góz mitt.” Þorgils hugsar, hvat um þetta er, ok veit nú, at þetta er einn uxi, ok var þetta þá kálfr, er hann gaf honum. Nú vaknar Þorgils ok ætlar nú at kasta útan borðs uxanum. En er Þorgerðr verðr vís, falar hon uxann, því henni var vistafátt. Þorgils sagðist vilja ónýta uxann ok engum selja. Þorgerði þótti nú illa. Hann lét kasta uxanum útbyrðis ok kvað eigi kynligt, þó illa færist, er fé Þórs var innbyrðis.

Thor answers: “Although you never do me any good, you will still pay me my goods.” Þorgils thinks about what this is about, and now knows that this is one ox, and this was a calf when he gave it to him. Þorgils now wakes up and is about to throw the ox overboard. But when Þorgerðr was certain, she kills the ox, because she was short of provisions. Þorgerðr said he wanted to make no use of the ox and sell it to no one. Þorgerðr now thought ill. He had the ox thrown overboard and said it was not wonderful, although it would be ill if Thor’s cattle were in the house.

The nature of Old Norse religion and worship was highly transactional and based on reciprocity. Much like the gift-giving reciprocity between men in the sagas, the deity and the worshipper were in compact with one another. The worshipper gives a sacrifice and then the deity gives an equal gift to the sacrifice. When the worshipper receives the gift from his god he is then obligated to give another one. The cycle then repeats.

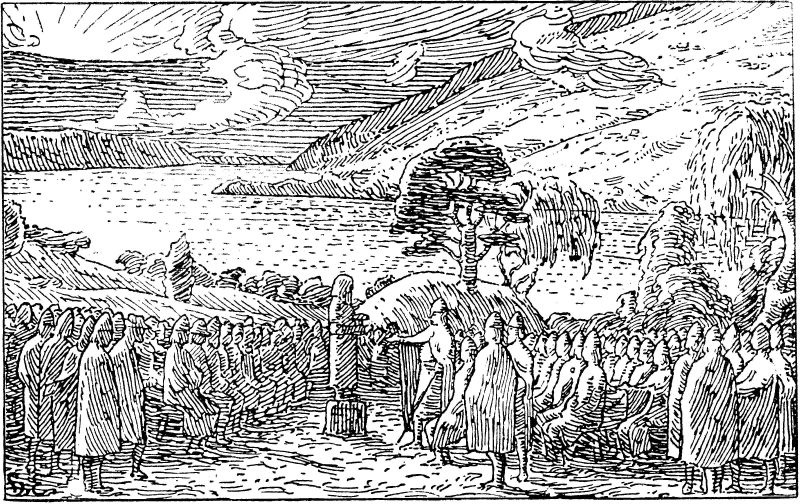

Moving on in the saga, Guðbrandr’s host bring the image of Þórr to the field, and when the farmers see this, þá hljópu þeir allir upp ok lutu því skrimsli — they then all leapt up and then bowed to the monster. The leaping up is a clearly joyous action at the sight of the god coming to the field, but the term lutu for bowing refers to prostration, a highly reverential action. The custom of prostration in the Þórr cult is noted in Kjalnesinga saga, where Þorsteinn Þórgrímsson is seen in the temple lá á grúfu fyrir Þór — lying on his belly before Þórr in worship. It is evident that the farmers were devout in their worship to warrant this behavior.

Guðbrandr then proceeds to taunt the king:

Hvar er nú guð þinn, konungr? þat ætla ek nú, at hann beri heldr lágt hökuskeggit; ok svá sýnist mér, sem minna sé karp þitt nú, ok þess hyrnings, er þér kallit biskup, ok þar sitr í hjá þér, heldr en hinn fyrra dag; fyrir því at nú er guð várr kominn, er öllu ræðr, ok sér á yðr með hvössum augum; ok sé ek, at þér erut nú felmsfullir, ok þorit varla augum upp at sjá. Nú fellit niðr hindrvitni yðra, ok trúit á goð várt, er alt hefir ráð yðart í hendi.

Where is your god now, king? I think now that he wears a rather low beard; and so it seems to me that your boast is smaller now, and that horned one that you call bishop, and that sits there with you, rather than the day before; because now our god has come, who rules over all, and looks at you with sharp eyes; and I see that you are now full of fear, and hardly dare to raise your eyes to look. Now cast down your hindrances, and believe in our god, who has all your counsel in his hand.

This speech gives a great perspective on the differences between how the sagas and Eddas depict Þórr. Guðbrandr here states that Þórr is an all-powerful god, stating that he öllu ræðr — rules all. This type of language exists in other sagas such as Sveins þáttr ok Finns, wherein Þórr is called the höfðingja allra goða – the chieftain of all the gods. This deviates from Gylfaginning 17, which states that Óðinn ræðr öllum hlutum — rules all things. Þórr often takes the central and chief role in the sagas, while Óðinn takes a more peripheral role. This element of his speech reveals that Guðbrandr’s region had a cultic focus of the god as a central deity, similar to that of the Þórsnesingar and other early settlers in Iceland.

The St. Olaf then has Kolbeinn the Strong strike the idol and mice, lizards and worms erupt from the image. Upon seeing this, the farmers are terrified and flee, running to their boats and horses, which are compromised at the St. Olaf’s doing. He bids them return, and then states:

Eigi veit ek, segir hann, hví sætir hark þetta ok hlaup, er þér gerit; en nú megi þér sjá, hvat goð yðart mátti, er þér bárut á gull ok silfr, mat ok vistir, ok sá þér nú, hverjar vettir þess höfðu neytt, mýss ok ormar, eðlur ok pöddur; ok hafa þeir verr, er á slíkt trúa ok eigi vilja láta af heimsku sinni. Takit þér gull yðart ok gersimar, er hér ferr nú um völlu, ok hafit heim til kvenna yðarra, ok berit aldri síðan á stokka eða á steina.

“I do not know,” he said, “what is the cause of this commotion and running about you have made; but now you can see what your god was able to do, the one to which you have brought gold and silver, food and provisions — and now you have seen what creatures have enjoyed it: mice and snakes, lizards and vermin. And worse off are those who believe in such things and will not give up their foolishness. Take your gold and treasures, which now lie here across the field, and carry them home to your women, and never again lay them upon logs or stones.

The terms of note here, are the use of stokka and steina. This describes the what the images of the gods were made of. The term stokka, from stokkr means a mast, trunk, beam, or log. This is refers to the depiction of the gods on pillars which is referenced in other sagas. The saga depicts Þórr being decorated with gold and silver, probably referring to gold and silver inlaid or overlaid engravings upon the image of the deity, or even gold leaf painted upon the image. Images made of stone were also painted, as archaeologists know that runestones were adorned with vibrant colors, with traces of the chemical composition of the paints still present on many runestones.